We're not bored enough

What we lose when we can't sit with ourselves

Last week I wrote about how rest became something I had to fight for, even though I work so hard to earn it. It was both heartwarming and a little disheartening how many people related to that article (if you took the time to comment, thank you <3). I’ve been thinking more about boredom and why it’s what we should all strive for, so this article is for those of us wanting to dive a little deeper into the psychology of boredom and why we need it.

What do you think about when you wash the dishes? What runs through your mind when you’re folding laundry? When’s the last time you drove in silence?

I often catch my mind racing through these mundane moments. While I’m washing dishes, my brain is already three tasks ahead—planning dinner, drafting an email, remembering something I forgot to do yesterday. And while dishes, laundry, and commuting were never meant to be the highlight of our lives, they are—well, life.

So what does it say about us when we can no longer find peace—or even just presence—in these already rare moments our schedule finally allows us to slow down?

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when stillness started causing discomfort, but I can bet our hyper-connectivity and obsession with productivity have made it much worse. We’ve been conditioned to equate productivity with worth and we measure our value by our output. No wonder moments without “doing” feel wasteful and unnatural. We’ve turned rest into something we have to earn; something to schedule and optimize.

Our brains have learned that life only counts when we’re checking something off a list, whether that’s finishing a work project or finally reading that book we’ve been meaning to get to.

Boredom is no longer even an option we allow.

There’s a deeper theory on the topic around how people will avoid gaps in their time because they’re afraid of being alone with their thoughts. When we’re bored, our minds naturally drift towards the future—planning, visualizing, imagining, and sometimes worrying. For some, that can be uncomfortable territory.

In a 2014 study published in Science, psychologist Timothy Wilson and his colleagues at the University of Virginia gave participants a choice between sitting alone with their thoughts for 15 minutes or pressing a button that would administer an unpleasant electric shock to themselves. 67% of men and 25% of women chose to shock themselves at least once during the 15 minute period. One participant shocked himself 190 times during the session.1

So how did we get here?

How did we become so uncomfortable with stillness that we’d choose discomfort over it?

On dopamine and reward systems

Having worked in tech, I’ve seen first hand how much time and effort gets put into figuring out how we can encourage users to use an app more often and stay in it for longer. Digital platforms optimize for dopamine-driven reinforcement through likes, notifications, gamifications, constant data, and endless scrolling.

And it works! Every ping, like, and new piece of content triggers a small dopamine hit in our brains—the same neurotransmitter involved in reward, motivation, and pleasure. Research shows that adolescents with internet addiction disorder have plasma dopamine levels twice as high as those in healthy controls. In other words, we’re not imagining it: our devices are literally changing our brain chemistry.

And here’s the kicker: dopamine isn’t just about pleasure but about the anticipation of it. It’s the potential that keeps us going2. Maybe the next post will be interesting. Maybe someone will comment on my photo. The lack of predictability keeps our brains in a loop, constantly seeking the next reward, the next hit.

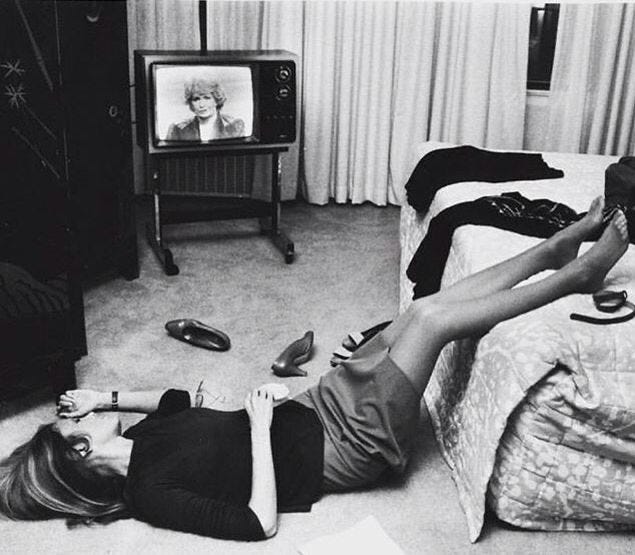

As we scroll and scroll and scroll, we’re training our brains to expect constant stimulation with an occasional dose of dopamine. On the flip side, when things are quiet something feels a little off. We’ve unintentionally created a missing feeling.

There are also studies showing that the mere presence of a smartphone can actually reduce our cognitive performance. When we’re trying to avoid usage and suppress our attention to the device, our brains are expending precious resources leaving less mental capacity for everything else. It’s gotten to the point where even when we’re not using our phones, it’s still taking up too much headspace.

Redefining boredom

Choosing boredom sounds counterintuitive because we’ve spent the last decade treating boredom like a disease. The clinical definition describes it as an attention or meaning deficit—a lack of interest, stimulation, or challenge that brings feelings of sadness, loneliness, and distorted time perception. That kind of boredom drains us.